There are thirty-four different members of the rail family that are listed as extinct. Rails are not strong fliers; these are medium-sized birds with short wings. Those species of rail that still are able to fly are generally easily blown off course, a characteristic that has led them to populate many isolated oceanic islands. In addition, these birds often prefer to run rather than fly. Many kinds of rails have therefore given up on flying altogether.

Flightlessness can save a bird some trouble, if they evolve in the right environment. Many island rails are flightless because small island habitats without predators eliminate the need to move long distances. Flying is difficult, and makes intense metabolic demands of a bird. Muscles used to fly can take up a large portion of birds weight, and giving it up can save a bird in energy expenditures. Flightlessness can make it easier to survive and colonize an oceanic island where food and resources may be limited.

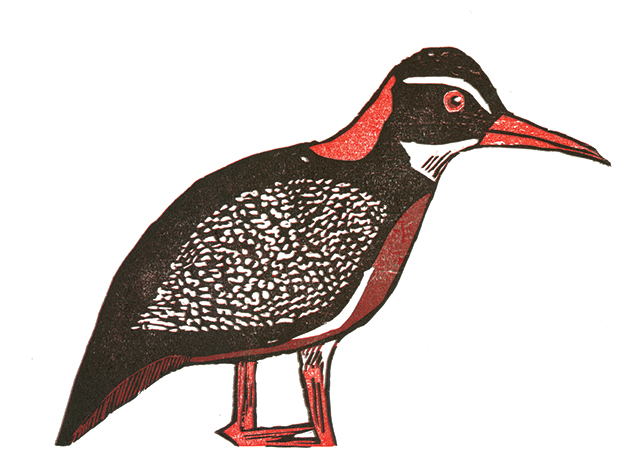

The sum total of what we know about the Tahitian Red-Billed Rail comes from a specimen picked up by Johann Reinhold Forster, famous naturalist on Captain James Cook’s second voyage. He brought his son Georg along for the trip, and Georg painted this:

George Forster – Scanned from the book “Extinct Birds” by Errol Fuller, 2000

That one specimen disappeared at some point.

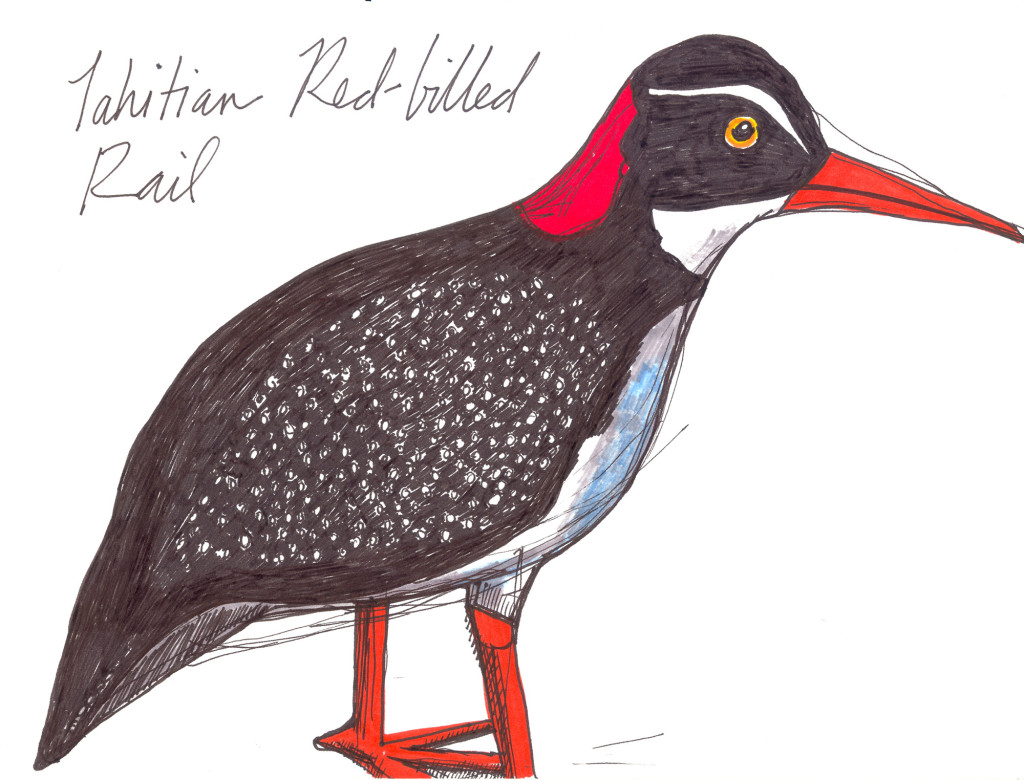

The painter John Gerrard Keulemans made his own cleaned up version based on Georg’s watercolor, which he had seen in the British Museum:

Restoration by John Gerrard Keulemans, based on Forster’s illustration Tahiti Rail Two-Thirds Natural Size—from Forster’s drawing in British Museum (Gallirallus pacificus) depiction by John Gerrard Keulemans from ‘Extinct Birds’ by Lionel Walter Rothschild from the year 1907.

Georg’s drawing was only one of many thousands of illustrations of Tahitian flora and fauna as well as the first map of the islands of the Pacific, all brought back during Cook’s three trips through the South Pacific. Europeans were fascinated by images of the foreign birds, plants and fruits encountered during the Age of Exploration. This is why Cook brought a naturalist on board on his voyages, to record impressions, observe, collect samples, and draw images of the flora and fauna they encountered. In the process, voyagers like Cook participated in an unprecedented, large-scale rearrangement of life on Earth: taking samples from one island, bringing them to another, taking along animals from home, leaving some along the way.

But what happened to the Red-Billed Rail? Unknown. We assume introduced predators did them in, like many flightless birds in the area. The rearrangement of species disrupted the life rails like this knew, and exposed them to risks they were not adapted for. We’re not sure when they disappeared, and how long they survived for.