Birding in Audubon’s time was about crazed amateurs tramping through an endless American wilderness, determined to draw every bird there was, or at least all the ones they could find. After Audubon his fans began to develop a professional class of bird enthusiasts, and the story behind birding shifted. Ornithology became a discipline, and men like Spencer Fullerton Baird and Elliott Coues began developing departments of ornithology in American institutions, starting membership-based professional organizations, and publishing lists of birds for professional ornithologists. Professional Ornithologist began to be a thing. Taxonomy was their primary concern; which birds were what and where did they live. Their books were heavy, not user-friendly, and aimed at a specific class of birder. Taxonomy and lists of species were developed systematically through the collection of specimens. Specimens were dead birds, several per species, intended to be examined and catalogued. New specimens were collected from the wild, sometimes by professional collectors, often by members of the military personnel busy measuring, patrolling, and surveying the Great American West. Specimens were shot and stuffed for study, and their value was in part assessed by their rarity.

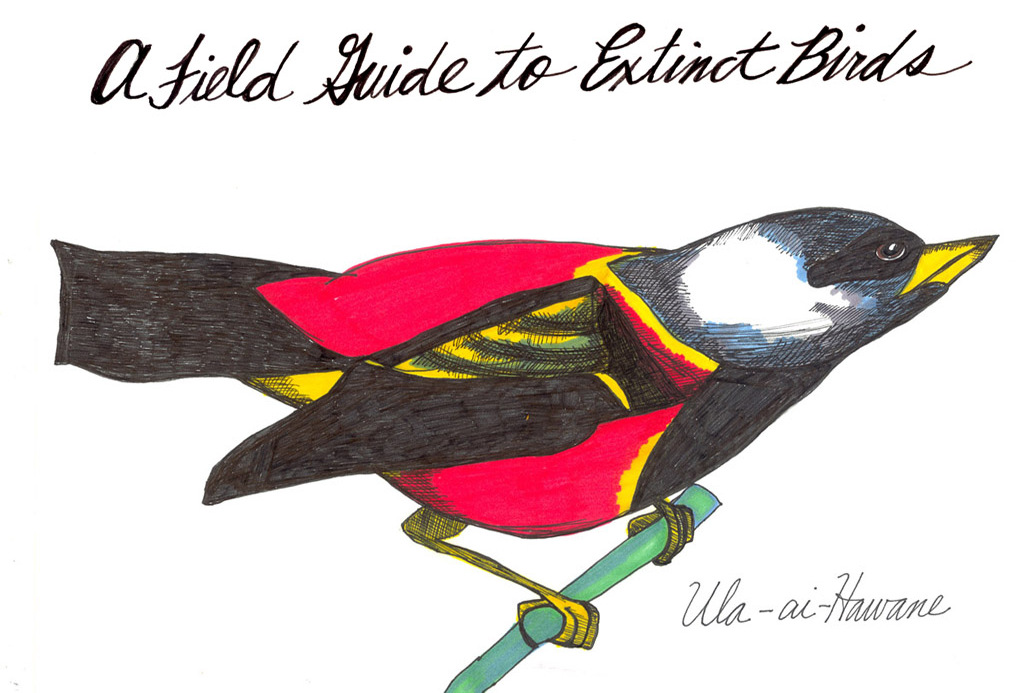

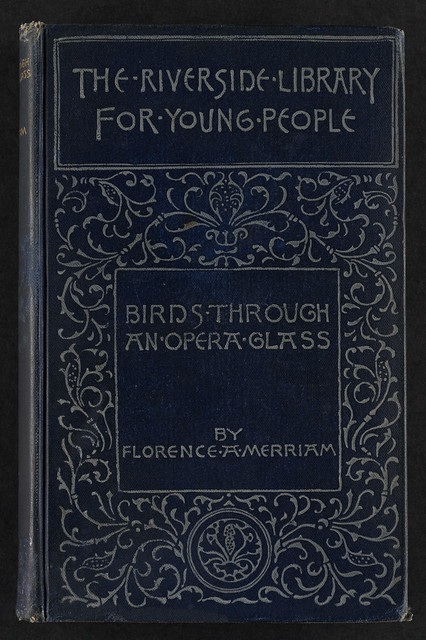

Women interested in birds, however, usually fell outside of this community. Some professional organizations refused to admit women, others admitted them, if they were sufficiently ornithological enough, but looked down on those birders who they referred to as “opera glass fiends”- the newly developing category of enthusiastic amateur. This was the (scornful) name that distinguished professional Elliot Coues used to refer to the first bird watchers, amateurs interested in learning about birds and bird behavior through watching living birds, and who did not hunt or collect specimens for study. Coues did however help some young women enter the field, including one credited with writing one of the first real field guides to birds. Florence Merriam organized the first Audubon chapter at Smith College while a student there; was the first female member of the American Ornithologists Union; and wrote a landmark book, Birds Through an Opera-Glass when she was only 26 years old. The purpose of this book, based on a series of articles that she had written for Audubon Magazine, was to introduce young people and women to living birds, observed in the field. It was illustrated with black and white woodcuts, easy to read, unpretentious, and useful. It is considered one of the first of the modern illustrated field guides, published by Houghton Mifflin in 1889.

The book focused on the excitement of watching birds, and their habits and behavior, not on collecting them. It described 70 common species, and included a key to identification in the field.

Merriam later moved out West as a cure for tuberculosis, and published further works: A-Birding on a Bronco (1896), Birds of Village and Field (1898), another guide for beginners focused on the birds of the West. She wrote the authoritative Handbook of Western Birds in 1902, which would remain a standard reference for at least 50 years. She included vivid descriptions of behaviors like nesting, feeding, and vocalization. Birds of New Mexico followed in 1928, for which the AOU gave her its Brewster Medal, its highest praise for ornithological research and the first ever bestowed on a woman.

Her last published work was Among the Birds in the Grand Canyon Country, published by the National Park Service in 1939. She and her husband, Vernon Bailey, Chief Field Naturalist for the United States Bureau of Biological Survey, traveled throughout the US and were together responsible for encouraging many youngsters to study natural history.